My daughter Maya, like many children with special needs, has

undergone (too) many evaluations. Her skills and knowledge have been

quantified, over and over again, with varying degrees of accuracy. Many parents

of children with special needs speak about receiving the evaluation reports

with a hint of PTSD in their voices and tears in their eyes. I see their posts

in Facebook groups, about a son who has “the cognitive functioning of an 18

month old” or a daughter with “very little receptive language, according to the

recent report.” Many have been devastated by these reports.

I am not one of these parents. I have not been devastated by

the reports.

Ok, the first one briefly knocked the wind out of me, but I recovered

quickly.

Why not? Perhaps because Maya’s scores have been promising?

Or “average”? Or “low average”?

No. No, not because of that. As a matter of fact, her first

round of cognitive testing was abysmal. She scored in the bottom 0.4th

percentile---meaning that 99.6% of all children her age were more cognitively

advanced than Maya. Her receptive language evaluation (at 2.5 years old) estimated

that she could produce 1-2 words and that she understood 1-2 words.

They said that she understood 1-2 words. At 2.5 years old.

I wasn’t gutted by the reports because I knew they were

worthless. At the time, I thought everyone knew they were worthless---that they

were just a means to an end (the end goal being to score “disabled enough” to

qualify for services). I thought the results were like She’s in the 0.4th percentile—wink, wink. It wasn’t

until I became more immersed in the special needs community, particularly the

community of parents who have children who are functionally nonverbal, that I

realized something startling---people are believing these numbers.

Parents, you cannot believe these numbers.

Not only will believing the numbers send you down some sort

of spiral-of-terrible-feelings, but believing them will change your

expectations for your child. The numbers will change what you believe your

child is capable of, they will plant seeds of poisonous doubt, and they will

corrode your ability to presume competence. If you have a child who doesn’t

speak, one of your biggest, constant jobs in life will be to advocate for their

people to believe in them . . . so if you start to lower your expectations,

others will follow.

Plus, really, the numbers are garbage.

My undergrad degree was in science (zoology), my first

master’s degree was in teaching secondary science, and I was a classroom

teacher for 8 years. This means that I have both spent a fair amount of time

reading scientific journals and that I have experience with assessments of

children (and their limitations). I listen to news stories with a skeptic’s ear

(who funded that study, what was the

sample size, how did they control for these 12 other variables, etc). I see

the limitations of a standardized test as quickly as I see the potential data

collected. I take all reports with a grain of salt, by nature. But when I saw

the way that Maya’s evaluations were done, I realized that it’s not just a

grain of salt needed when looking at cognitive assessments (or receptive

language assessments) of nonverbal kids, it’s a mountain.

Let’s think about the

tests: If an evaluation is being done on a child who can’t functionally speak,

can’t read, and can’t write, answers to questions would basically be limited to

two methods of production: pointing to

an image in a field (which item would you use to drink?) or completing performance

tasks (such as arranging tiles to match a pattern). There are significant variables

in both of these models that can result in scores that are erroneously low---false negatives.

pattern sheets that would be used with tiles

Performance Tasks: It’s easy to see why the

performance tasks would result in low scores for many of our kids. The only

examples that I clearly remember were about using tiles/blocks to duplicate or

continue patterns. For a child like Maya, who struggles to use her fingers to

manipulate anything small, this was a very challenging task. She also has apraxia, which means that the messages from her brain to her muscles get derailed---so she could be thinking "move the tile forward" but her hand won't respond. When we got to these questions, Maya refused to try

and put her head down.

So, did her inability to engage with the task indicate that:

a) she didn’t recognize the pattern

b) she didn’t

understand the question

c) she didn’t want to try a task that would be simultaneously

cognitively taxing and physically close-to-impossible

Who knows. But for

scoring purposes, that’s a fail. This is a false

negative. The absence of a positive response in this situation doesn’t reliably

indicate a cognitive limitation, but it will be scored as one.

Pointing at pictures: When I first saw a flipbook

that would be used to evaluate receptive language, I thought it looked like a

great idea. Maya was probably around 2 years old when I saw the test

administered, and while I sat silently and didn’t interfere, I was surprised by

how something that at first glance seems fairly straightforward and objective

was actually very subjective and unreliable. There are a few things that need

to be taken into consideration when thinking about these tests.

1. Personality: Children with complex communication needs

often have a fairly passive personality with regards to getting their point

across (due in large part to the fact that other people--parents, siblings,

teachers--often step in to try to communicate for them). In addition to being

passive, our kids learn that sometimes acting clueless is a great way to avoid

the task at hand (hours of therapy reinforced this for Maya---act clueless, the

therapist will adjust the task or change to a new one). While I can’t speak for

all nonspeaking kids, Maya mastered “the blank stare” (in which she would

simply stare around like she didn’t hear anyone and had no knowledge of what

was transpiring around her) at a young age. I will never forget watching a new therapist

try to cheerfully get Maya’s attention to give her back her car keys: Maya! Maya, over here! Those keys are shiny,

right?! I’m going to need the keys back now! Hey, Maya! and then I was all Maya, quit it and give her the keys and

she looked up and handed them over. If a child stares blankly at an evaluator and doesn't engage with the test, that is not necessarily indicative of a lack of understanding. It's a false negative.

2. Modified abilities lead to modified experiences: One page of the receptive language test had images of art related items (crayons, scissor, glue, etc) and Maya was asked to identify the scissors. Maya

didn’t know what scissors were when she was two---she was an only child who

spent all of her time at home with me and in home therapy, and she had

basically no fine motor ability. She had never seen scissors. This is only one

example, but there were several. Did she

know what scissors were? No. Was this indicative of her ability to understand,

absorb, and recognize language? Of course not. It was indicative of the fact

that her atypical abilities were leading her through an atypical childhood. It

was a false negative. (I bet typical kids don’t know what chewy tubes or

z-vibes are---Maya would have nailed those ones.)

3. A will, but not a way: For kids with disorders like apraxia or other neurological conditions, there are times when their body does not follow the directions being sent out by their brain. They may be thinking "reach out and touch the scissors, reach out and touch the scissors" but then see their arm reach forward and their hand make contact with the glue. If I stand up and quickly spin in place several times, no amount of me thinking "now run in a straight line!" is going to make that actually happen. It's a physical limitation. Modifications can be made to tests and testing environments to attempt to minimize these effects, but neurological motor planning troubles must be taken into account as a possible source of false negatives.

4. Communication vs. Testing: Children who are functionally

nonverbal are often very interesting communicators who use a variety of methods to get their points across:gestures, sights, sounds, meaningful glances, avoidance. One thing that tends to be

fairly consistent is the ability to communicate via pointing and pictures: even

before Maya used picture cards or communication technology, she could

communicate by pointing to the pictures in a book. She pointed to the cow, I

would say “A cow! Mooooo!” She pointed to the moon, I would say “That’s the

moon! It comes out at night.” Or, outside of books, if she pointed to the

refrigerator, I would say “Are you hungry?”

During these tests our children are presented with a field

of images and asked a question that has an “obvious answer”. The problem is

that presenting a nonspeaking person with a field of images can be akin to

saying “Check these out! Which one speaks to you? Which one reminds you of

something? Which one do you want to talk about?”

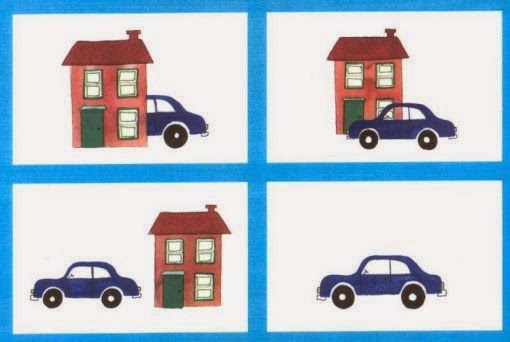

I'm willing to bet that if I showed this to Maya and said "Which picture shows the car in front of the house?" she would point to the first picture, look pointedly at me, and laugh. Translation: "Mom! There's a car driving into a house! This is ridiculous! . . . Wait, did you ask me a question?"

Example: Maya was 2(ish) and was in the middle of a

receptive language test. The doctor flipped the page and said “Which one is the

hairbrush?”, and Maya pointed to the toothbrush instead of the hairbrush. Obvious

wrong answer, obvious confusing of one "brush" with another, right? No, not right. We

had been talking about tooth brushing at home all morning. We had read a book

about going to the dentist. We had bought a new toothbrush the day before. When

the doctor flipped the page and asked about a hairbrush, Maya was already

fixated on the toothbrush (which looked just like hers, by the way) and

reaching toward it. As she tapped it, she turned to make eye contact with me. I

saw her saying Look! A toothbrush, just

like mine! We were just talking about brushing teeth! The doctor saw the

wrong answer. A false negative.

Parents, take heart. Professionals, take heed. There is no

reliable standardized way to assess the receptive language or cognitive function of a person

with complex communication needs. Even now, with a robust language system, Maya

has a way of seemingly jumping to unrelated topics that are actually related (but their relation is something that only she would know). Here’s a final example: On Tuesday Maya went to her after-school speech therapy,

and this happened:

Therapist: “How was school?”

Maya: (glancing at the fire alarm over his head, in the corner

of the room, and then using her device

to spell) “f-i-r-e.” (copied from the side of

the alarm box)

Therapist: (looking up at the alarm) “Yes, that says ‘fire’ .

. . but let’s focus-I asked you how your

day was. Did you have a good day at

school?”

There was no way for him to know that her school had a fire

drill that morning.

He thought she wasn’t paying attention, but she actually was

telling him about her day.

False negative.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.PNG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.PNG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpeg)

.JPG)

.jpeg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)